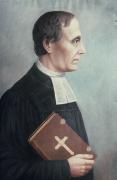

The journey of Hermann Kemp and Wilhelm F. Schwarz has been immortalised in a booklet called Venture of Faith. This epic trek traversed around 900 kilometres of unforgiving terrain from Bethany in the Barossa Valley, South Australia to the Finke River; with 37 horses, 20 cattle and nearly 2000 sheep, five dogs and chickens.

Kemp and Shwarz could hardly have known what they were getting into when they set out. The journey was laborious taking 20 months and was undertaken at the hottest and driest time of year. Construction began on the first building in late June 1877 using wood and reed grass. It was later that year in November before construction began on the first stone building which served as the mission kitchen.

The missionaries intended that the mission become as self-sufficient as possible. Having survived the arduous journey north themselves, they were understandably concerned about the costs of haulage from southern ports for any supplies they would require. With this in mind, by May 1878, a well and irrigation system was installed to supply a garden which grew maize, melons, cabbages and lettuces and fruit trees.

European settlement increases along with atrocities against Aranda people

By 1879, all the land surrounding the mission had been occupied by cattle stations. This had several implications for the mission. While the mission land holdings were large, approximately 233,099 hectares or (900 square miles (2,300 square kilometres), and later expanded to 310,799 hectares or (1200 square miles (3,108 square kilometres), the Arrarnta’s (Aranda as it was called then) traditional territory covered a much larger area. The lifestyle and indeed sustainability of the Arrarnta people was based on this large territory which allowed for seasonal fluctuation of resources particularly waters sources, food and ceremonial sites.

Aboriginal people came in from the bush drawn by kinship ties and driven by the impact of droughts combined with the pressure on native game and water resources due to the surrounding cattle industry. As cattle stations sprung up commandeering large tracts of traditional land and in many cases forcibly ejecting Aboriginal owners from their land. Tensions mounted as more Aboriginal people congregated around the mission. Toward the end of 1883 there were serious outbreaks of hostilities between the Aborigines and white station owners and many Arrarnta were slaughtered. Missionary Kempe was appalled at the situation surrounding the mission and gloomily predicted:

"In ten years’, time there will not be many Blacks left in this area, and this is just what the white man wants. With all the looting that is taking place, it is hard to conceive that the native people have any kind of future, and our only hope is that they are rescued from this intolerable position."

The mission became a place of refuge for Arrarnta people in that they were protected somewhat from the graziers and the police.

Early Achievements

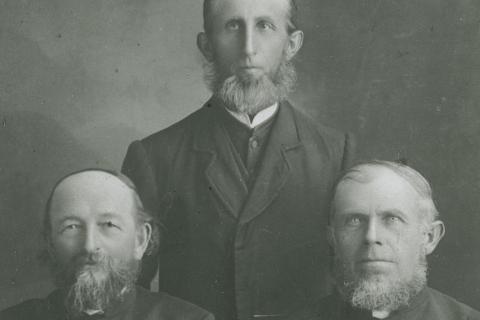

Despite a lack of resources, isolation and limited support from the wider church establishment there were a number of remarkable achievements at Hermannsburg Mission. By 1883, there were 21 mission personnel and, in addition to the buildings they constructed mainly from local materials, they could also claim other achievements, including a number of Arrarnta language publications. These included:

- a 21-page primer for use in the school published in Adelaide in 1880;

- Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language Spoken by the Aborigines of the MacDonnell Ranges, South Australia – published in 1890 Royal Society of South Australia;

- the first book of Christian instruction in Arrarnta compiled by Kempe in 1881 printed at Hermannsburg in Germany;

- a book entitled: The Aborigines of the Upper and Middle Finke River: Their Habits and Customs, with introductory notes on the physical and natural-history features of the country was published in 1890 by Schulze.

Hardships took their toll on the health and morale of missionaries

As one might expect, the mission suffered its share of setbacks and tragedies, A disastrous drought was experienced in 1880 which destroyed most of the crops and many of the mission personnel contracted scurvy. In fact, drought was a common occurrence and the struggle for a secure water supply persisted for many years.

The harsh conditions affected the health of many of the missionaries who had originally travelled from the much cooler climates of Germany to serve at Hermannsburg. One by one the missionaries succumbed to the harsh conditions in Central Australia. Schwarze left with his family in September 1889. Schulze, his wife and their five children left in November 1891 due to illness. In 1890, Kempe suffered a severe attack of apoplexy and then in 1891 he contacted typhoid fever. In November 1891 his wife died a few weeks after the birth of their last child. Thirteen days later Kempe left Hermannsburg with five of his children leaving the baby behind with the lay worker Eggers’ family. On 11 September 1893, the lay worker Holtermann left due to illness and three days later Eggers and his children also left.

With the departure of the key drivers, the mission entered a period of decline with no investment and little direction. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, there were fractures emerging between the Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Australia (ELSA) and the Hermannsburg Society in Germany and it was proposed in 1893 that the Finke River Mission be sold, and proceeds divided between the parties. After various deliberations, the Finke River Mission was offered for sale to Immanuel Synod for the agreed price of £1500.

- Lohe M 1977 Hermannsburg a vision and a mission. Lutheran Publishing House Adelaide p17

- Scherer 1975:80

Media